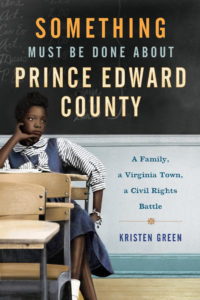

Kristen Green took an uncomfortable look at her home county’s anti-integration past in the 2015 book Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County. (Dean Hoffmeyer)

By Edie Gross

For years, newspaper journalist Kristen Green ’95 covered stories about inequality in poor, minority communities around the country. But one story she hadn’t yet tackled nagged at her.

In 1959, her Virginia home county had closed its public school system rather than integrate its classrooms. Perhaps, Green thought, it was time to turn her reporter’s eye on the role her own community – and her own family – had played in perpetuating racial segregation.

There was a book there, she knew.

She’d read historical articles detailing Prince Edward County’s refusal to desegregate as part of Virginia’s so-called “massive resistance” to integration. And she’d begun grappling with the realization that her beloved grandparents, Mimi and Papa, had been part of an effort to shut black children out of school.

Green’s friend and Mary Washington classmate Jane Archer ’95, a Brooklyn-based designer and illustrator, created the book’s cover.

Papa had passed away while Green was a student at Mary Washington, and Mimi was ill and unwilling to talk about the past. But Robert Taylor, a longtime friend of her grandparents and a co-founder of the whites-only academy that essentially replaced the county’s public school system for five years, was open to a conversation.

Seated in Taylor’s Farmville den in November 2006, Green asked him whether he regretted helping deny black children an education. His answer stunned her: He declared that he was still a segregationist and that maintaining the purity of the white race was as important to him in 2006 as it had been 50 years earlier. Taylor died a few weeks after that interview.

Now, nearly a decade later, Green acknowledges that she probably should have anticipated the man’s unapologetically racist response.

Over the next eight years, she’d hear plenty of equally defensive retorts while working on Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights Battle.

Along the way, subjects accused her of digging up ancient history and rubbing salt in old wounds. But Taylor’s words stung more than most, maybe because Green had known him since she was a toddler, or maybe because he was the first to give voice to an ugly undercurrent she knew still coursed through her cherished hometown.

The Rev. L. Francis Griffin of First Baptist Church visits with children at a “training center” set up to reinforce basic academic skills while Prince Edward County’s public schools were closed. (Richmond Times-Dispatch, 1960)

“It hit me at some point that this was going to be really hard. He talked about black boys dating white girls and getting them pregnant and white girls’ families being stuck with these babies they didn’t want. He called them ‘pinto babies.’ I walked away just kind of stupefied,” said Green, who only two years earlier had married a multiracial man.

“That conversation made me realize how painful writing the book would be, doing the research would be.”

It would be more than a year before Green would conduct another interview. By then, she and husband Jason Hamilton had welcomed the first of their two daughters. Green knew her family’s history, complicated or not, would also be her daughters’ history, and that meant she had to confront it.

The author’s daughters, Selma and Amaya, stand with Elsie Lancaster, a longtime housekeeper for Green’s grandparents. During the school shutdown, Lancaster had to send her own daughter away from home to get an education. (Kristen Green, 2013)

Harper published the book in June 2015. Part memoir, part history, it details the events leading to the county’s controversial decision to close all its public schools from 1959 to 1964. And it looks at the fallout for the community, primarily its black residents, who struggled to catch up when schools reopened or never returned to school at all.

Woven throughout are Green’s efforts to reconcile the adoring grandparents of her idyllic childhood with their unrelenting support for segregation.

“All the ingredients were there,” said Gail Winston, an executive editor at Harper, who praised Green’s personal approach to a painful history. “It’s sort of a brave book, and I think the passion of that comes across in her writing.”

Green grew up knowing precious little about the firestorm that enveloped Prince Edward County decades before her birth.

In 1951, students at the county’s all-black high school went on strike to protest inferior and overcrowded conditions. The NAACP filed a lawsuit, which was eventually combined with four other cases from across the country into the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas.

The court ruled unanimously in May 1954 that segregated public education was unconstitutional. But Virginia, following the stance of former governor and U.S. Sen. Harry Byrd Sr., adopted a policy of “massive resistance,” and it would be years before any of its schools integrated.

Even after most communities throughout the state grudgingly yielded to federal court orders, Prince Edward County rejected desegregation. In 1959, the county’s board of supervisors voted not to appropriate money for the public school system. Meanwhile, white leaders made good on a plan they’d been formulating since the Brown ruling five years earlier, establishing a K-12 whites-only private school known as Prince Edward Academy.

Green’s grandfather helped found the academy and sat on its board for at least 25 years. Both of Green’s parents graduated from the school. And even after public schools reopened in the fall of 1964, most of the community’s white students would continue for decades to attend the private school, including Green and her three younger brothers.

Green said she grew up knowing that her grandparents helped found the academy in the wake of public school closures so their children’s education would not be interrupted. But no one acknowledged that it was a living, breathing monument to the years of education denied the community’s black children.

Green had no black neighbors and until the eighth grade, no black classmates.

The only black person she knew was her grandparents’ housekeeper, whose heartbreaking decision about how to secure her own daughter’s education is featured in the book. But as a youngster, Green was blissfully unaware of her hometown’s ugly past.

It wasn’t until she attended Mary Washington, Green said, that she learned to question authority. As a reporter at the student newspaper, then known as The Bullet, Green realized that just because sources were nice didn’t mean they were truthful.

Classmate Jane Archer ’95, a Brooklyn-based designer and illustrator, remembers Green as an affectionate young woman with a wide smile who would loudly declare “Well, that’s just wrong!” if she felt someone was being treated unfairly.

“She’s fearless. It’s one of the things I’ve always admired about her,” said Archer, who met Green as a freshman in Virginia Hall and remains one of her closest friends. “She’s always felt like family to me, from Day One.”

In what she calls a “really awesome full-circle moment,” Archer, who had worked with Harper’s creative director before, was invited to submit some cover designs for Green’s book, including the one that was ultimately chosen.

After graduating with a degree in American studies, Green pursued a career in journalism, taking her reporting and writing skills to newsrooms in Virginia, Oregon, California, and Massachusetts. In Salem, Oregon, she covered burgeoning gang violence in the Latino community. She later wrote about immigrants and the refugee population for the San Diego Tribune, taking a four-month leave of absence to study Spanish in Guatemala before returning to take over the newspaper’s inner-city beat.

While out West, her thoughts turned to the history of her own hometown. How, she thought, could she tell the stories of so many other communities and not share the story of her own?

The more she read about Prince Edward’s past, the more committed she was to writing a book.

About 2008, while working on an assignment for her master’s in public administration at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, Green picked up a copy of They Closed Their Schools, a 1965 book about Prince Edward’s reaction to the Brown decision. Until then, she said, she’d believed that her grandfather had simply followed the lead of other white community members in helping to start the private Prince Edward Academy.

But in the book, he’s described as a founding member of Prince Edward’s chapter of the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties, a grassroots organization dedicated to preserving segregated schools.

“That was a game-changer for me. My family was deeply involved too,” said Green, who moved to Richmond with her husband and daughters about five years ago. “I was wrestling with all this Southern baggage about loyalty and the meaning of family. What do you do with this kind of information? I loved my grandfather deeply. How do you share these stories and still be respectful?”

Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History William B. Crawley Jr. said his History of the South class covers many of the events detailed in Green’s book.

Green does a solid job of weaving her personal narrative with the community’s history and doesn’t shy away from the “unpleasant realities” of her family’s story, Crawley said.

“I think she needs to be commended for her honesty about what for her was clearly a traumatic discovery. She didn’t back away from it, and she was not deterred by the possible backlash of people in her community and in her own family,” he said. “That takes courage.”

Her family’s response has been mixed. Though the topic has been uncomfortable for them, her parents have supported her efforts, she said. More distant relatives have told her they would’ve preferred the story not be dredged up.

Overall, she said, the response has been positive. Professors around the country have told her they plan to roll the book into their lesson plans. She’s heard from white graduates of the former Prince Edward Academy, now called Fuqua School, who have thanked her for sharing the school’s troubling history. She’s also heard from black residents of Prince Edward County, some of whom had never before shared their stories of truncated educations or the trauma of being sent away to live with strangers so they could stay in school.

“It was more than just denying children an education. It was denying them familial relationships,” Green said.

It’s important, she said, to own the mistakes of the past. “We have a lot of work to do in this country, grappling with unpleasant history. I felt there is nothing wrong with feeling shame or guilt about things your family has done in the past, to fess up and to talk about it,” she said. “I thought it was the right thing to do, to say what my family did was wrong and I’m sorry.”