The steep and seemingly endless stairs that lead to the maze of rooms on the fourth floor of Cooper Square do not faze Jones. At 77, she walks or bikes almost everywhere.

On a gray, wet morning in January, her bike was wedged in the narrow place between the wall of the building and the first-floor staircase. There used to be more room for it there, Jones said, until a luxury hotel went up around her home. Hotel investors had wanted to demolish the tenement altogether. Jones and another long-time resident didn’t want to leave, and the hotel couldn’t kick them out. The architect modified his plans to envelop the building.

Jones unlocked her apartment, walked into the kitchen and set down The New York Times, bought from a corner store on the brisk walk home from breakfast at a café just a few blocks away.

The Times, she confided to a visitor, is her obsession, although at $2 a day it has become a pricey habit.

She put down her wet umbrella and the book bag that doubles as a purse. She changed out of her sensible walking shoes.

The night before, Jones and her older daughter, Kellie – both writers – had been the featured speakers at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Afterward, they had signed books for audience members and gone out to dinner. Jones got in later than she is accustomed to these days.

Hettie Jones’ home is like a museum, except there is no pretention in the artifacts and you are allowed to gaze on them up close. There is a farmer’s sink and a rocking chair (once pulled from a fire) next to the kitchen table. There are baskets of books. There’s a claw-foot tub in the bathroom.

A discarded tabletop on a giant wooden spool is the coffee table.

A large photo of two pretty, dark-skinned girls on the Cooper Square rooftop – the daughters of Hettie and her former husband LeRoi Jones – hangs in the kitchen above the washing machine, watching over it all.

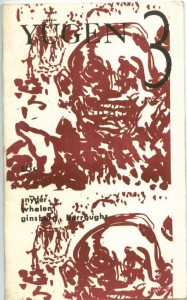

A half-century earlier, Hettie and LeRoi Jones hosted big parties in these rooms. At 27 Cooper Square, and in their earlier New York City flats, they gathered Bohemian artist friends to make merry and assemble, page-by-page, the couple’s hip literary magazine, Yugen. Then, you could find pre-fame Beats and New York School figures like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, Diane di Prima, Gary Snyder, and Joel Oppenheimer between the oddly configured walls and between Yugen’s pages.

Hettie Cohen Jones and then-husband LeRoi Jones published Yugen from their home with the help of writer friends whose poems and stories filled the pages of the literary magazine.

Inside their anything-goes circle, Hettie and LeRoi drew admiration for their talent and sometimes respect for their mixed-race marriage. America viewed them differently.

It was in this Cooper Square home that Jones looked out on a gentrifying East Village and wrote her 1990 memoir, How I Became Hettie Jones. The book landed on the New York Times’ list of 200 Notable Books of 1990 and still is taught in university classrooms. At her desk, Jones wrote the poems that made up her first book of poetry, Drive, which came out in 1999 and won the Poetry Society of America’s Norma Farber First Book Award. By then, Jones was 62, had been divorced more than 30 years, and had raised the two daughters she and LeRoi Jones had together.

The wooden secretary is nearly indistinguishable among the books and papers and little trinkets in Hettie Jones’ study – a bowl of paper clips, a tiny metal bicycle, bits of wit and inspiration framed or taped to the walls. As Jones needed more space to work, she expanded the little oak desk with random furniture and pieces: a buffet table sits at one end, a wooden board on file-cabinet legs at the other. She has arranged all of this into a giant U-shaped writing space and set out photographs of herself.

There is Hettie at age 4, squinting into the sun; Hettie at 14, at summer camp in the Adirondacks; Hettie in the early 1950s at Mary Washington College; and Hettie, the young mother, reading to her little daughters.

At 77, she likes to look back on who she used to be. “These are versions of myself in my life that I never want to disappoint.”