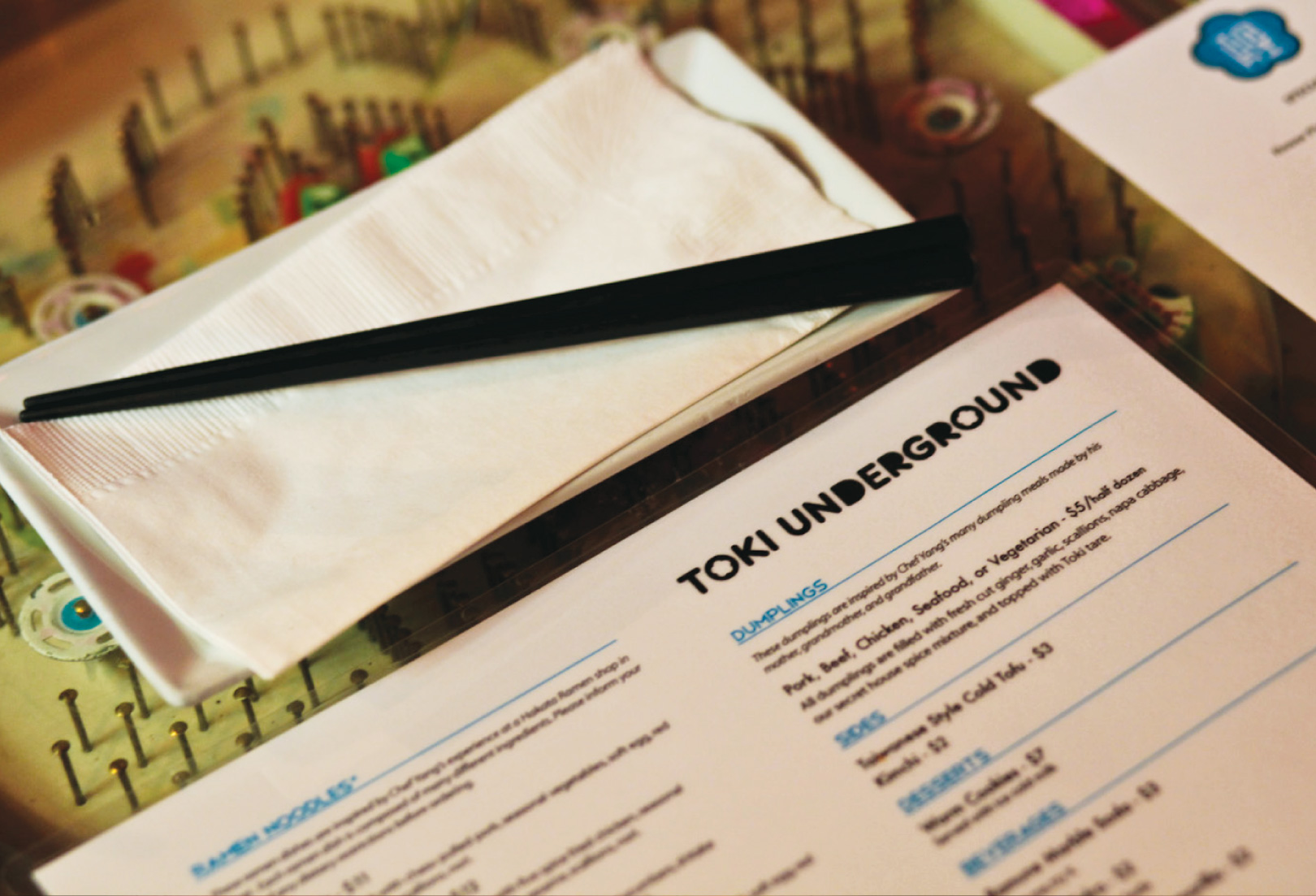

Erik Bruner-Yang opened Toki Underground, a Taiwanese-style noodle shop, in 2011. Today, customers wait for hours for his freshly made ramen. Photos by Dayna Smith.

It’s five hours before Toki Underground opens its doors to customers, but the cubbyhole of a restaurant perched above a bar along H Street in Washington, D.C., is already busy.

Inside the impossibly small kitchen, owner and chef Erik Bruner-Yang ’07 and a colleague dump buckets of pork marrow bones into cavernous metal pots and set them to simmering on the stovetop.

Behind them, a third member of the team chops fresh vegetables that will season steaming bowls of ramen later that evening. A few feet away, a fourth sorts curly strands of noodles into uniform piles.

The restaurant’s bar is papered with invoices as deliverymen come and go, dropping off beverages, crates of plastic carryout containers, and bunches of fresh ginger, garlic, and mustard greens.

The deliveries come daily to 1234 H St. NE for two reasons. First, Bruner-Yang will use only the freshest ingredients when whipping up dishes like mom used to make.

Second, at 675 square feet, the tiny Toki Underground − Washington Post food critic Tom Sietsema referred to the space as a “shoebox” − lacks a walk-in freezer and much else in the way of storage space.

“We pretty much start from scratch every day,” said Bruner-Yang, fueling himself with a Diet Coke during a brief break. “We just make it all over.”

It’s an exhausting process. Bruner-Yang is 28, but he jokes that his knees are 40.

Still, it’s a recipe for success. Since the place opened in April 2011, diners have regularly waited two hours or more to snag one of the restaurant’s 30 coveted bar stools. And afterward they’re still happy enough to post effusive comments on Toki Underground’s Facebook page.

“My friends and I once showed up on a super busy night and were 30th on the waiting list . . . and we waited anyway!” gushed one customer. “It is THAT GOOD, people!”

“Go here. Now. Seriously,” insisted another.

A different fan wrote, “Thank you for existing.”

Readers and the editorial team at Eater DC voted Toki Underground its 2012 Restaurant of the Year. The Post’s Sietsema declared it “the best ramen in the city,” and a recent New York Times travel piece urged D.C. visitors to swing by the restaurant.

On top of that, Toki Underground is where the chefs eat. The really famous ones. Like legendary Peruvian chef Gastón Acurio, Spaniard Ferran Adrià − who’s been called “the world’s greatest chef” more than once − and D.C.-based José Andrés of minibar, Zaytinya, and Jaleo fame.

And it didn’t hurt when actor Neil Patrick Harris, in the capital in early December for the national Christmas tree lighting, tweeted to his more than 5 million followers about his visit to Toki Underground.

And it didn’t hurt when actor Neil Patrick Harris, in the capital in early December for the national Christmas tree lighting, tweeted to his more than 5 million followers about his visit to Toki Underground.

“Sake, dumplings, tofu, and utterly delicious ramen. A must go,” he announced, posting a photo of his mouth-watering meal for good measure.

That prompted one D.C. foodie to respond: “Let’s all thank @ActuallyNPH for making the acceptable 4hr weekend wait @TokiUnderground now a somewhat acceptable 6hr wait.”

Bruner-Yang shrugs off the celebrity encounters.

“NPH is only going to come once. People like you are more important because they’re more likely to come back,” he told a visitor. “Every day’s a chance to get another regular.”

WHAT WENT IN THE BROTH

Running one of D.C.’s hottest new restaurants wasn’t part of Bruner-Yang’s original career plan.

A native of Taipei, Taiwan − where much of his mother’s family still lives − he was a Navy brat who lived for a time in California and Japan before settling in Northern Virginia during the fifth grade.

As a senior at Woodbridge High School, he’d visited the Mary Washington campus and liked the vibe, so he applied for admission as an early decision candidate.

“It was the only college I applied to,” said Bruner-Yang, who ended up rooming with childhood pal Jon Bibb ’06 in Jefferson Hall.

Bruner-Yang had played in a band in high school, and he figured he’d pursue a career in music. Once on campus, he and Bibb met Merideth Munoz ’05. They formed the popular indie pop/rock band Pash, with Bruner-Yang on guitar, Bibb on drums, Munoz behind the mic, and first Ryan Little ’07 and later Ryan McLaughlin on bass.

Their energetic live shows garnered a loyal following first from Mary Washington and then from Fredericksburg and beyond. The band managed to tour and cut several albums before members − by then, Joe Ostrosky was playing drums − went their separate ways in 2010.

Washington City Paper’s Aaron Leitko alerted readers to the final show, which was at D.C.’s Black Cat, and mourned Pash’s passing. “Seven-and-a-half years is a pretty long and full life for a band − plenty of time to traipse about the country, play dingy basements, and memorize the Waffle House menu,” he wrote. “But it’s still hard to say goodbye.”

Before he was a chef, Bruner-Yang was lead guitarist for Pash, a band born at Mary Washington in 2002. Pash played its farewell gig at D.C.’s The Black Cat in 2010. Here Bruner-Yang is shown with members, left to right, Ryan McLaughlin, Merideth Munoz, and Joe Ostrosky. Photo by Shantel Mitchell.

Aside from music, the other constant in Bruner-Yang’s life was the food-service industry. He’d waited tables throughout high school. In fact, he showed up at the registrar’s office as a freshman with a backpack full of cash − $4,500 in ones, fives, and tens − planning to pay for his first semester with the tips he’d earned. Clerks asked him to return with a cashier’s check.

He financed subsequent semesters with money he earned at a series of jobs at downtown Fredericksburg restaurants: Hyperion Espresso, Sammy T’s, J. Brians Tap Room, Claiborne’s, and Merriman’s Restaurant and Bar. He did everything from washing dishes to preparing food. And what he didn’t spend on tuition, he often plunked down on music at Fredericksburg’s Blue Dog Records and Tapes.

On campus, Bruner-Yang rotated through majors, trading music for English, then switching to anthropology, sociology, and finally business administration.

“I floated around all the liberal arts classes and picked the one class I got an A in,” he said, laughing.

Business Professor Leigh Frackelton remembered him as a student who somehow balanced work and musical gigs with business law and accounting classes.

“He was a cool kid, and I knew he had to work during school because he’d come in exhausted to class,” Frackelton said. But, he added, Bruner-Yang never let his exhaustion get in the way of his inquisitive nature.

He asked lots of questions about going into business for himself, Frackelton said. And if Bruner-Yang didn’t get answers in class, he’d swing by Frackelton’s office to inquire further about music copyrights or how best to set up a corporate entity.

UMW Associate Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean of Student Life Cedric Rucker knew Bruner-Yang from Pash and through a sociology class. He remembers him as engaged and creative − and interested in forging his own path.

“He was bright. He was inquisitive. He was a doer. He was always out there just trying to make it happen,” Rucker said. “He was picking up skills, learning to be innovative and blending it all together for his life. That’s the virtue of a liberal arts education. It allows for that experimentation. You find that thing that gives your life meaning.”

MAKING PLANS

Bruner-Yang worked restaurant jobs to earn his way through UMW. He showed up freshman year with a backpack full of tips – ones, fives, and tens – to make his first tuition payment.

With his bachelor’s degree in hand, Bruner-Yang moved to D.C., where he worked as the general manager of Sticky Rice, opening the restaurant’s H Street location only doors from where his Toki Underground stands today.

He also tended bar and partnered in a pop-up style operation; he and several friends ran a temporary taco stand out of an H Street ice cream shop that had closed for the winter. The place had no indoor seating, but that didn’t keep the crowds away.

“People stood outside in the snow to get their tacos,” Bruner-Yang recalled.

By then, he’d been mulling over going into business for himself for years.

“I always liked working in restaurants,” he said, “and I thought, ‘If I’m going to work this hard, I should be my own boss.’”

At first, he thought he might like to open a dumpling shop and bar, so he went ahead and leased the tiny former hair salon along H Street that is now Toki Underground. He feared that if he waited until his entire business plan came together, someone else would snag the spot. He started saving his money, making pitches to potential investors, and running through the list of do’s and don’ts he’d learned working in other people’s restaurants.

“Every mistake I could’ve possibly learned, I learned on someone else’s dollar,” he said. “The rest was, ‘How do we not make those mistakes?’ ”

In 2009, Bruner-Yang traveled back to Taiwan for a month to be with his grandfather, who was ill. An uncle, knowing his nephew needed a diversion outside the house, secured him a job at a nearby ramen shop. There, Bruner-Yang absorbed lessons about how to run a business and how to create a top-notch product.

“I learned a lot through watching,” he said. “When I came back, that’s when I said, ‘It’s going to be a ramen shop.’ Still, we didn’t really know what we were doing. I knew how to make soup for like eight people. We were doing 100 or more a day.”

A considerable amount of buzz preceded Toki Underground’s April 1, 2011, opening. While many associated ramen with the cheap packages of dried noodles they’d consumed in a college dorm, Bruner-Yang’s menu boasted five rich broths adorned with a mouth-watering assortment of fresh ingredients: red pickled ginger, braised pork belly, shiitake mushrooms, scallions, sesame, seaweed, and homemade kimchee.

In addition, inspired by the meals made by his mother and grandparents, Bruner-Yang offered plates of pork, beef, seafood, chicken, and vegetarian dumplings − six for $5. With bowls of homemade soup running $11 or $12, Toki Underground’s prices are more than reasonable by D.C. standards.

The menu, which includes warm cookies and cold milk for dessert, has remained relatively simple.

“Most restaurants fail,” Bruner-Yang said, “so we don’t want to mess with the formula too much.”

COMFORT FOOD IN A COMFORTABLE SPACE

His customers − and restaurant reviewers − don’t seem to mind.

In a September piece forThe Village Voice, reviewer Robert Sietsema − a distant relative of The Washington Post’s Tom Sietsema − praised the Taiwanese comfort food and the “pleasantly cramped space that makes you feel instantly at home.”

Bon Appétit magazine declared Toki’s ramen “world-class.” “The bowls of noodles are accomplished, fully realized cooking, which is why you’ll see chefs from other restaurants here after hours.”

Bibb, Bruner-Yang’s former roommate and the original drummer for Pash, dropped by Toki Underground for a meal before leaving for Peru to serve in the Peace Corps. The long lines and fantastic food didn’t surprise him.

“Erik has always been someone who just naturally knows what is cool or hip and also someone who loves to entertain people. [When we were in Pash together,] he loved performing and putting on a show. And I think people really enjoyed watching him. I have to believe that some of that is what makes his restaurant successful,” Bibb emailed from Peru. “He likes to entertain people and he knows how to. He’s just a hardworking guy with a passion for entertainment and a natural talent for creating pleasing products, be it music or food!”

Mary Washington graduate Megan Parry ’05 enjoyed a meal at Toki just before the holidays with her business partner, Alicia Austin Morgan, and their husbands.

“We thought it was awesome. It was cool to be there on a cold winter night and share a big warm bowl of noodles,” Parry said. “It’s a fun place to be.”

The restaurant’s neighborhood-hangout aesthetic − with its graffiti-covered walls, red paper lanterns, open kitchen, and skateboard-decks-turned-foot-rests − appealed to Parry and Morgan, who own Forage, a downtown Fredericksburg shop that specializes in vintage clothing and accessories. At the urging of a mutual friend, they asked Bruner-Yang if they could bring some of their items to his restaurant for a pop-up show one Sunday, when Toki Underground is normally closed.

“I felt like I was asking a huge favor,” Parry said. “But from the moment he emailed me back, ‘Let’s get it done,’ we got it done in one month.”

The Dec. 9 event − the first for Forage − was a success. Bruner-Yang, a pop-up veteran himself, said he loved partnering with Mary Washington grads who, like him, are making a living pursuing their passions.

Bruner-Yang hopes to do more collaborative events to promote art, music, and other projects along the H Street corridor, where he lives. The D.C. community has a small-town feel, not unlike Fredericksburg, he said, and networking with others and supporting their efforts is not just a good idea. It’s “a moral obligation,” he said.

To that end, he often joins forces with other chefs for charity events. The Saturday night before President Obama’s Jan. 20 inauguration, Bruner-Yang was one of seven chefs whipping up specialties at the Chefs Ball, which raised money for a number of good causes, including D.C. Central Kitchen, the James Beard Foundation − a nonprofit that promotes the culinary arts − and Common Threads, which teaches children from low-income families how to create affordable, nutritious meals.

Back at Toki Underground, the crowds are steady, with regulars and new diners lining the narrow staircase to the second-floor restaurant six nights a week. Bruner-Yang met his fiancée there when she stopped in for a meal. He employs 22 people to keep up with customer demand, and he provides health insurance for most of them.

“I love coming to work,” Bruner-Yang said. “I think it would not be as fun if the crew wasn’t as good. But everybody wants to see the place do well.”

He and his investors have considered moving to a larger space, but they like the cozy environs − even if working in the minuscule kitchen requires a delicate choreography. Bruner-Yang envisions Toki Underground as a reasonably priced neighborhood hangout, bathed in the comforting scent of homemade broth.

“Every great neighborhood in any part of the world should have a place, a comfort food spot,” he said. “In Fredericksburg, you can grab a beer at J. Brian’s or a bite at Sammy T’s. My ultimate goal in establishing this restaurant is providing for the community that I live in − H Street.”

What an inspiration! I am a high school teacher and I will be sharing your story with my students. You show that anything is possible. WELL DONE!