By Kristin Davis

Just a few years after college graduation, Jacqueline “Jaci” McClain Kelly ’06 had achieved most everything she’d dreamed of.

She’d launched a career, putting her Mary Washington political science education to work as a project analyst for a government contractor. She’d married Darryl Kelly, her sweetheart ever since he’d brought her a corsage on their first date to a high school banquet. They’d started a family.

But when Darryl’s work with the Air Force meant a family move to Wichita, Kansas, Jaci knew it was time to fulfill her most ambitious goal.

Since childhood, she’d dreamed of becoming a lawyer. Maybe the dream started in Newport News, where she grew up in the loving embrace of an aunt and uncle who raised her as their daughter. Or maybe the dream started even earlier, on a farm in southwest Zimbabwe, where Jaci’s grandfather glimpsed in his tiny granddaughter the intelligence and spark of a scholar.

And now, with a husband whose career sometimes meant months-long deployments, with three young children of her own, and with the nearest law school two hours away, Jaci was more determined than ever. She enrolled in the Washburn University School of Law and committed to the struggle of juggling family, classes, the long commute, and late nights poring over law texts.

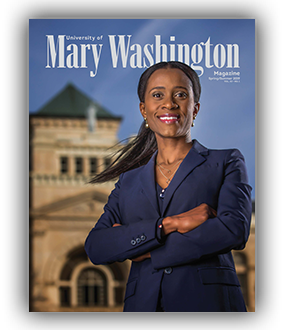

She graduated in 2014 and launched the career that led her to become city attorney in Bel Aire, Kansas, where she provides legal counsel for city officials.

Jaci Kelly’s life today looks and feels a lot like the American dream. And it is. But the dream was never Jaci’s alone.

_____

In her earliest memories, Jaci roamed the 17 sprawling acres of her grandfather’s farm, with vegetable gardens and livestock and a house that seemed as big as the dreams it held. It sat on the outskirts of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, where her grandfather, Samuel Ncube, was headmaster of a primary school.

The farm was the center of 4-year-old Jaci’s universe. It was the home where her father was raised and the place she and her cousins played board games and hide-and-seek. Twice a day, the family gathered around the dinner table to share stories in their native Ndebele.

Years later, Jaci would understand the purpose of these mealtimes – rituals that taught her warmth and strength and the meaning of family. The daughter of unmarried teenagers, Jaci had been placed in the care of a grandfather. He believed that education was the only way to make it in the world, that families make sacrifices so that the next generation has more opportunities than the last.

Even if it meant sending his youngest grandchild halfway around the world so that she might have a chance to make a mark on it.

_____

A few years earlier, Samuel Ncube had also sent his first-born daughter, Yvonne, out into the world, to England to become a nurse. There, she was recruited to work at a hospital in America.

After two years as a nurse in Las Vegas, Yvonne visited a cousin in Hampton, Virginia, where she met Ricky “Sipho” McClain, a mailman and Air Force veteran. They married, and in 1987 they headed to Zimbabwe for a honeymoon.

Samuel Ncube surprised the couple with a traditional African wedding and a life-altering request. He was getting older, he told them, and couldn’t give Jaci everything she needed. Would they be willing to take her with them to America?

Yvonne wanted a daughter. Ricky told his bride he’d treat her brother’s child like his own flesh and blood.

When her grandfather first introduced Jaci to Yvonne and Ricky, the youngster – who Yvonne said always had a mind of her own – wouldn’t stay with the couple. “She said she’d come back Tuesday,” Yvonne said. “She did. From that day on, she was with us.”

In January 1988, Yvonne and Ricky returned to Virginia as parents of the newly turned 5-year-old girl they called their wedding present.

Jaci remembers that the flight was long. She remembers that the buildings in Virginia were big, the people diverse. She remembers feeling curious and excited. She does not remember feeling sad or homesick.

In Virginia, Yvonne bought her new daughter smocked dresses with ruffled sleeves and headbands to match her blouses. She decorated her bedroom entirely in purple because Jaci said she liked the color. She filled it with dolls and toys.

Quietly, though, Yvonne worried. Jaci was set to start kindergarten that fall, and she didn’t know English. Yvonne enrolled her in preschool and hoped it would be enough.

When kindergarten started, Yvonne scheduled a parent-teacher conference, expecting a problem. When she explained that Jaci had been in the U.S. less than a year, the teacher looked back, confused.

There was no problem, she told Yvonne. Jaci had not just acclimated. She was flourishing.

_____

There were family trips to Florida and Washington, D.C., birthday parties and home-cooked meals around the family table. When the weather was warm, Yvonne, Ricky, and Jaci – and later, two of her biological brothers, Sam and Khosi, whom her aunt and uncle also adopted – made day trips to Yorktown Beach, where they splashed in the water and played games and picnicked in the shade. On the Fourth of July, they stayed after nightfall, watching the fireworks light up the dark.

But studies came first; Jaci never forgot what she’d come here for.

In fifth grade, Jaci made her first trip back to her birthplace. She’d been gone half her life, but she took up where she left off, playing with her cousins and roaming the familiar acres of her grandfather’s farm.

Grandfather Ncube had stayed in close touch with his granddaughter despite the distance. Her self-described “uncle-dad,” Ricky, sent him a stream of photos of the youngster and her successes. Her grandfather died two years later, knowing that his granddaughter was fulfilling his dream for her life and education.

On that first trek back to Zimbabwe, Jaci visited her birth father, a man who loomed like a hero in her earliest memories.

“I remember just wanting to be with him, memorizing everything about him,” Jaci recalled. “I remember riding in his car. He liked country music.”

She saw her birth mother on that visit, too – an intense reunion between Jaci and a now-grown woman who’d started a separate family.

Jaci would not see either of her birth parents again. Zimbabwe, once the breadbasket of Africa, was slipping into political and economic turmoil. Inflation and unemployment soared, health care became scarce, and people of her parents’ generation struggled.

“There were things they were dealing with that I for sure couldn’t understand,” Jaci said.

She next returned to Zimbabwe as a teenager, for her father’s funeral. “This is the saddest I can ever be in my life,” she thought.

Jaci reminded herself that she’d loved him. That he would have been proud of who she was becoming. She wondered what might have become of her if not for Yvonne and Ricky, if not for her grandfather’s vision. It was her vision now, too.

_____

She lingered over the one from the University of Mary Washington, a school halfway between Richmond and Washington with columned buildings, brick sidewalks, and an air of prestige.In high school, Jaci filled her free time with extracurriculars – the Mayor’s Youth Commission, the National Honor Society, the Lions Club, nearly 1,500 hours of volunteer work in four years. She began sorting through college brochures.

On a clear day in April 2000, Yvonne, Ricky, and Jaci took a tour of the Fredericksburg campus. A snapshot taken outside Seacobeck Hall captured blossoming trees and beaming parents. The family would visit 10 universities before picking the one that felt just right.

“I was meant to go to Mary Washington,” Jaci said. “I could find myself. I could thrive.”

UMW was, above all, a place where she could feel confident and bold – capable of great things. She received a partial merit-based scholarship.

“You can’t help but go after your dreams and succeed.”

At Mary Washington, professors challenged her, made her stretch. Victor Fingerhut, now associate professor emeritus of political science, was an expert in political theory and public opinion and a Yale University alum.

Distinguished Professor Jack Kramer took no nonsense. “Learn and understand the history, the issues, the context,” Jaci remembered him telling political science students. “Once you get that, then you can tell me what you think.”

After graduating in 2006, she launched a career and married. She and Darryl welcomed a child, then two more, in the span of six years. Jayda came first, followed by Darryl III (they call him Trey), and Janae.

In 2009, the young family moved halfway across the country, to Wichita, where they gathered around the dinner table each night just as Jaci had done, first as a child in Zimbabwe and then in Newport News. Today, the Kellys’ lives center on homework, the children’s many activities, and ballgames that Darryl coaches.

Jaci chairs the board of trustees at PBS station KPTS and is vice chair of the parent group at The Independent School, which her children attend. She’s active in the local chapter of Toastmasters, too.

The Kellys make sure their children have even more opportunities than they did, furthering the family vision that each generation should surpass the one before it.

Jaci can still remember the look in the eyes of Ricky and Yvonne, who traveled to Kansas to see her graduate from law school.

“There was a peace about them,” Jaci said, the kind that comes when a family fulfills its dreams.