Hettie Roberta Cohen was the seconddaughter of Oscar and Lottie Cohen, a middle-class couple who settled in the mostly Jewish Laurelton neighborhood of Queens. Lottie was a homemaker who cooked and cleaned and laundered for the family when many of the neighbors hired out those chores. Oscar manufactured cardboard advertising displays.

By the time she was 14, Jones wanted to get away; by 17 she’d decided to attend an all-women’s college. She whittled her choices to New York’s Vassar College and Mary Washington, and she was accepted at both. Jones chose Mary Washington for the picturesque campus photographs, because it was farther from home, and because it cost less. And, she added, “I was afraid Vassar would make me a snob.”

The girl from Queens arrived in Virginia in 1951, three years before the Supreme Court outlawed school segregation in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education. Until then, she had never been farther south than New Jersey.

“I felt very much the Yankee Jew from New York,” Jones wrote in her memoir.

The only African-Americans she saw regularly were the women who cleaned the Mary Washington dormitories. To pick up extra money, one black woman ironed students’ skirts and blouses. As she had done with her mother, Jones ironed her own clothes in the laundry alongside the woman, who always met her with a smile and who taught her how to navigate the tucks in her blouses.

In Fredericksburg, Jones was shocked to see an auction block, once used to display human chattel, preserved at the corner of Charles and William streets. “As a northerner, I didn’t know what to think,” she said. “I was appalled.”

We’ve always taken care of our people, she remembered a Southern classmate saying of the black women who worked in her family home. We send our people to the dentist.

“I thought, ‘No, you pay them enough to go to the dentist,’ ” Jones said. “ ‘You don’t put them in that position. They are not subservient.’ ”

Jones majored in drama and speech at Mary Washington. She made friends and got involved in student groups. Despite feeling like an outsider, she was popular. Her freshman year, the student newspaper featured Jones, calling her a “well-known personality on campus.” The Bullet continued, “She is as explosive and as active as an A bomb, otherwise how would she find time to engage in so many extra-curricular activities and to do them successfully?”

The paper reported that she did “extensive work in drama” and had interests in music and art “from Picasso to ‘Pogo,’ and all types of books.” She was vice president of her sophomore class and historian of her senior class. She was a member of the dramatic fraternity, the honorary speech fraternity, and the Players drama group.

The Bullet reported in another piece that Jones led her Westmoreland Hall dorm-mates to victory in a campus singing competition and that she wrote, directed, and performed in “class benefits” musical shows.

“One night, awed by the reach of my own arm, I led a thousand young women in song,” Jones wrote in her memoir.

In 1954, a new drama professor, Albert R. Klein, started an experimental children’s theater at Mary Washington, and Jones directed the first play and others. The college provided her a bus, and she took the show on the road to country schoolhouses and veterans hospitals. She brought live theater to folks who’d never before experienced it.

At Mary Washington, Jones found her voice.

“At a woman’s college, you get to grow your sense of self,” she said. “Speaking your mind was something you were required to do. I felt so comfortable that I did not have to compete with the pretty girls for the attention of the boys.”

Jones (center), literary editor of The Battlefield yearbook, with fellow editors Alice Orem ‘55 and Joan Darden ‘55. (Photo from The Battlefield, 1955)

Jones was Battlefield yearbook literary, layout, and copy editor. She shared a dorm room and one desk with two roommates, so she staked out a place of her own in the Battlefield’s basement office. She retreated there in the evenings, longing to write plays but settling for poetry. Four of her poems were published her senior year in the Epaulet, the college literary magazine. Jones was Epaulet humor editor, and the magazine had published her byline earlier on short stories such as A Cool Tale for Crazy Cats.

The Bullet newspaper reported that Jones, with her high grade-point average and special classes, “was among the few girls who are doing Honors work at Mary Washington.” On the title page of her 135-page honors thesis – double-spaced, footnoted, and neatly typed on onionskin paper – Jones thanked drama professors Klein and Mark R. Sumner for their advice and assistance. The paper, written about poetry in theater, is still in the stacks at Simpson Library.

After graduating, a confident Jones returned to New York to start her life. She announced to her family her plans to move to Manhattan and get a job.

The Cohens were proud of their younger daughter but couldn’t understand why she didn’t want to “settle down.”

Jones found work at a film library and began graduate classes at Columbia University. After a year, her job lost funding, and she’d had enough of Columbia. At 22, she took a job as subscription manager for the Record Changer, a cool jazz magazine in Greenwich Village.

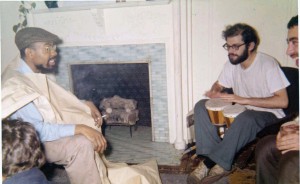

Jones married LeRoi Jones (above, left), later named Amiri Baraka, and kept company with literary greats like Allen Ginsberg (above, right). Allen Ginsberg Collection, likely taken by Peter Orlovsky

There Jones met and fell in love with LeRoi Jones. He stopped by the Record Changer office one afternoon looking for work. She was supposed to talk to him about the shipping manager job but never got around to it. He commented on the book Jones was reading – Kafka’s Amerika – and they didn’t stop talking about it until the owner of the place showed up an hour later.

LeRoi Jones was an aspiring writer, smart and quick and comfortable with himself. He was hired.

LeRoi and Hettie married in 1958, when marriage between blacks and whites was a crime in most states. That same year in Caroline County, Va., just 20 miles from Hettie Cohen Jones’ alma mater, a white husband and his black wife were roused from their bed, arrested, and jailed for having been legally wed in Washington, D.C. Their case went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In New York, the Joneses were subjected to disapproving stares and comments. Oscar Cohen insisted his daughter divorce. Lottie Cohen visited on occasion from Queens but told her daughter she would suffer and pay every minute of her future for the taboo life she had chosen. In Newark, N.J., Anna and Coyt Jones welcomed Hettie Jones as a daughter.

Hettie and LeRoi led the lifestyle of the time and the place – and they helped invent it. They were surroundedby jazz and art and passionate friends who filled their apartment by the dozens. There were writers and artists and musicians who’d stop in for a night and stay for a week or two.

“Downtown was everyone’s new place,” Jones wrote in her memoir.

New art showed up in storefront galleries. New writers read groundbreaking poetry in cafés, and actors performed new plays in “new nook-and-cranny theaters,” she wrote. “The jazz clubs were there among all of this.”

The Joneses had two daughters. Kellie came first. “It was very clear she was viewed as a black person,” Hettie Jones said. “We got stared at a lot.”

When Lisa came two years later, “we really got stared at. People realized this is not an accident. This is a family.”

LeRoi’s career took off and Hettie, who’d always taken pride in her independence, tended their home and their children. She took uninspiring jobs to pay the bills.

Influenced in part by the Cuban revolution, by Malcolm X, and by his own family’s suffering in white America, LeRoi Jones moved away from the Bohemian life with Hettie and toward Black Nationalism. He began to see himself less as an artist and more as an activist, and he changed his name to Amiri Baraka.

Yugen ended in 1962. LeRoi and Hettie’s marriage ended three years later, soon after the murder of Malcolm X.

“By the fall of 1964, black Americans were being asked to make choices. Nearly a decade of nonviolent protest had failed,” Hettie Jones wrote. “In the seven years I’d been with Roi, I’d watched the loosening of what would one day be called ‘black rage.’ … Now some people were beginning to say that hypocritical Roi talked black but married white.”

In a letter to her dear friend Helene Dorn, wife of poet Ed Dorn, Hettie Jones wrote of the separation, “It would have been easier to die except for the kids.”

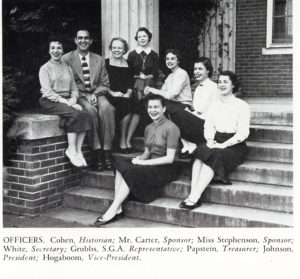

Jones was the 1955 class historian and was pictured in The Battlefield (far left, in white sneakers) with fellow class officers and faculty sponsors.

Both Hettie and Helene had in many ways lived in the shadows of their husbands. Both went through divorces in the mid-1960s. And both found their creative voices again. Dorn became a sculptor. Jones went back to her desk.

Six years later, Hettie Jones published her first book, The Trees Stand Shining, Poetry of the North American Indians.

Big Star Fallin’ Mama: Five Women in Black Music came three years later, and so did its distinction among New York Public Library’s Best Books for Young Adults. Jones later co-authored Rita Marley’s memoir, No Woman No Cry: My Life With Bob Marley.

Jones taught at Hunter College of the City University of New York and the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility. Today she is on the creative writing faculty at the New School, and she holds private memoir-writing classes at 27 Cooper Square. Jones practices yoga. And she takes time for family, especially 7-year-old granddaughter Zoe. “The delight of my life,” Jones said.

Most days she still finds time to sit at the desk, open her laptop, and write. She is working on a follow-up to her memoir, which ended as the newly single mother recovered from the break-up of her marriage and refocused on herself. The new book will tell another chapter through a generation of letters between Jones and Helene Dorn, written in spare moments they carved out late at night.