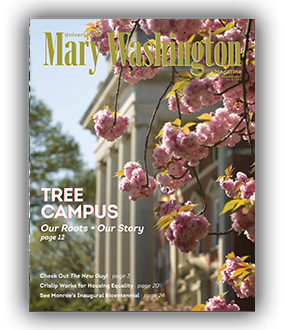

Cherry blossoms and spring midterms hit campus about the same time, giving students something peaceful to look at between study sessions at the Hurley Convergence Center. (Photo by Norm Shafer)

By Laura Moyer

The story of trees on the University of Mary Washington campus starts with the Brompton Oak – the Civil War “witness tree” famously photographed in 1864 as Union soldiers recovered beneath its branches. The venerable white oak has been thoroughly fussed over. It’s protected from lightning, its limbs are cabled for stability, and the lawn above its roots is roped off during public events. Decades ago, some well-intentioned souls even filled its hollow spaces with concrete.

Every Mary Washington president who’s lived at Brompton, from Morgan Combs to Troy Paino, has gazed on the tree with admiration and maybe a bit of anxiety.

For the past 30 years, Director of Landscape and Grounds Joni Wilson ’00 has shared those feelings as the person chiefly responsible for the Brompton Oak. She’s joking – or maybe not – when she says that if the oak died “I’d be gluing leaves onto it.”

But she’s been equally protective of other Mary Washington trees, from the magnificent willow oak on Ball Circle to the gnarly old mulberry near Randolph and Mason halls to the workaday red maples that dot the Fredericksburg campus.

As Wilson nears retirement at the end of this academic year, she’s making peace with the idea that she’ll no longer be the chief guardian of the university’s most permanent living residents.

“It’ll be fine,” Wilson said, as if to convince herself. “It may be different, but it’ll be fine.” (Story continues below.)

Wilson leaves a legacy of advocacy for campus trees during a major period of renovations and new construction. With each project, Wilson has insisted that architects and contractors consider the impact on trees. She’s pointed out that the trees standing in a building’s new footprint aren’t the only ones affected; nearby trees are also susceptible to root trauma and inadvertent wounds from heavy equipment.

One notable example of Wilson’s successful advocacy is that there are still two original silver linden trees on the Ball Circle side of the University Center, which opened in 2015 on the site of the former Chandler Hall.

Those lindens are an important connection between the present and the past, said Michael Spencer ’03, an assistant professor in the Department of Historic Preservation and author of a campus preservation plan detailing the university’s buildings and landscape.

The surviving lindens are the oldest intentional plantings on campus, Spencer said, dating to the institution’s 1908 beginning as the Fredericksburg State Normal and Industrial School for Women. They were planted to line the original entrance to campus, and they greeted generations of students, professors, staff, and visitors.

Spencer noted two other campus species with exceptional historic significance: The rows of Eastern red cedars that probably are vestiges of old fence lines predating the campus, and the pecans planted near faculty residences in the early years.

When alumni remember that they love how the campus felt, Spencer pointed out, they don’t just mean the buildings. “The trees, like the buildings, make up this cultural landscape.”

On a recent stroll along Campus Walk, from Double Drive to the Simpson Library and back, Wilson pointed out tree after beloved tree.

She started with the massive willow oak near the entrance to George Washington Hall. “I love it because of all its warty weirdness,” she said.

“Those mulberries … the big river birch over there … I love the pecans … those two big pin oaks in front of Westmoreland Hall … the loblolly pines … the Atlas cedar …”

At Virginia Hall, she pointed to a sourwood, a native tree with white panicles in spring and beautiful color in fall. “It’s just a great tree,” she said. Nearby are two yellowwoods, which sometimes bloom in time for commencement. Though they’re the same species, they don’t look exactly alike – one shows off a zebra-striped bark that’s especially dramatic when the leaves are gone in winter.

“I love this magnolia, too,” Wilson said, admiring the larger of the trees that stand sentry at Monroe Hall. Some members of Wilson’s crew sigh over the Southern magnolias because they’re so messy, shedding glossy leaves year-round and dropping seed-filled fruit that has to be raked up. But the fuzzy buds in spring and fragrant white flowers in summer make up for it.

Besides many delightful native dogwoods that dot campus, Wilson noted a few remaining Kousa dogwoods – trees she gave up planting after she decided they were mistakes. “They’re beautiful, but they bloom late, and they’re non-native,” she said. “They make a big, fat fruit that ripens and the birds can’t eat it.”

There have been other frustrations. Some landscape trees just didn’t thrive where they were planted. Others were chosen for a particular spot because of a predicted height or color that failed to materialize.

“That’s horticulture,” Wilson said with a shrug. “The trees never read the books.”

Wilson herself has read plenty, and she readily calls to mind Latin names and information about the roots, bark, foliage, and seeds of dozens of tree species. While working full time on campus, she earned a Bachelor of Liberal Studies degree from Mary Washington, graduating in 2000. She’s learned even more over the years from observation, experience, and her own self-directed study.

Of course Wilson’s job covers more than trees. She’s in charge of UMW’s sustainability efforts, and she supervises a staff of 20 people responsible for the landscape and grounds at Brompton, the Fredericksburg campus and athletic fields, the Stafford campus, the Dahlgren campus, and other college-owned properties.

She has great respect for the crews who do the hands-on work and put in long hours during storms or in preparation for major events such as commencement. “They know their stuff,” she said. “They really get that we’re a major part of supporting the mission of this university.”

Many of them have come to share Wilson’s passion for the trees, bushes, and plantings that lend color and harmony to the campus. They’ve internalized the belief that “the landscape has a really significant impact on the people who live and work here,” she said.

Besides setting an example of advocacy for faculty, staff, and her own employees, Wilson has partnered with students and community members interested in the natural resources of campus. Groups such as Tree Fredericksburg, the Fredericksburg Tree Stewards, the Central Rappahannock Master Naturalists, professional tree services, and the city of Fredericksburg have contributed.

Recently, the Tree Stewards – extension-service trained community volunteers led by Kevin Bartram, director of the UMW Philharmonic Orchestra – numbered and documented 535 trees in 52 zones of campus, filling spreadsheets with data on individual specimens.

And over the past two years Wilson has collaborated with Professor of Biology Alan Griffith on an experiential learning project that uses geographic information service mapping tools and software to create an online map of the campus’s “heritage trees.”

Under Wilson’s leadership, UMW has twice been officially designated a Tree Campus by the Arbor Day Foundation, an honor recognizing exemplary tree management, student engagement, and service learning. UMW is one of only four Virginia college campuses to receive the designation.

All these things give Wilson some comfort as she contemplates the future – her own, and that of UMW’s remarkable tree campus.

“I love this place, but you know, there are ideas other than mine,” she said. “Change is good.”

Thanks for the well disserved article, Joni revolutionized the Grounds Department. She improved efficiencies by advocating employee training and purchasing high performance equipment. Not many people know that she was one of the snow plow drivers. I enjoyed working with her and I wish her, Harold, and Sky (GO JMU) the best!