Tek loved the research that went into preparations for tournaments. And the rush of adrenaline that followed. “It’s like riding a roller coaster,” she said. And on the debate team, an insecurity that had plagued Tek since childhood – her rapid-fire speech – was suddenly an asset.

Tek enrolled in her first human rights class that same year and met the man who would become her mentor: Gregory Stanton, then the UMW James Farmer professor of Human Rights.

Stanton had lived in Cambodia in the early 1980s. The professor and the student quickly connected, Tek said. She enrolled in a second class taught by Stanton, and then a third.

“I took all of his classes and then some,” she said. Like other Mary Washington professors, and like Tek’s mother, Stanton taught lessons rooted in personal experience. “Mary Washington has a superb and very rich group of academic professors,” Tek said. “I was always pushed to do better, even if I got an A on a paper. It’s not so classroom-based. It pushes you to pursue things outside of grades. You felt like you were learning outside of the classroom, outside of a textbook.”

In Stanton, she said, “I had someone who could show me the way. I wasn’t as lost.” She learned life doesn’t have to be so one-dimensional. “You can take many paths in life.”

During her senior year at UMW, Tek studied abroad at Richmond, the International University in London, and interned in the English capital for an organization called Minority Rights Group International. Her policy debate research aided her there. It paved the way for her role as a research intern who specialized in East Asian minority issues, Tek wrote in her Fulbright application.

Still, she wrote, “I hungered for more direct involvement in the real, global struggle for human rights.”

That’s where the Fulbright came in.

“I thought it was unattainable,” Tek said. Then a friend attended a Fulbright information session and brought back an application. Tek contacted Stanton, who had once won the coveted grant. He helped her craft a research proposal.

Tek got the Fulbright.

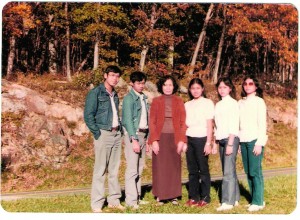

Sany Nhem (in skirt) and five of her children in 1983, after they came to the U.S. The family had survived forced labor, starvation rations, and the genocide that killed nearly one-quarter of the Cambodian people. Sophi Monh, who is just to the right of her mother, was only 8 years old when the Khmer Rouge took power.

With the backing of the international educational exchange program sponsored by the U.S. government, Tek would spend a year working in outreach programs of the ECCC’s victims unit. The ECCC “recognizes the role of victims more than any other international criminal court in history,” Tek wrote in the proposal.