Hope has been a powerful influence in the life of Richard Arline ’77.

Richard Arline ’77 was a Fredericksburg policeman with children when he started college on the GI Bill.

He had it as young teen in the early 1960s, when his mother let him leave their North Carolina home for high school in the Northeast. He had it as an enlisted Marine fighting in Vietnam.

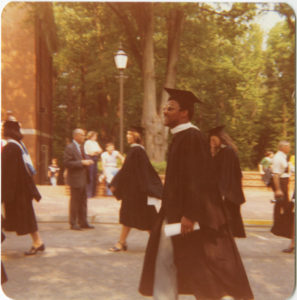

And he had it as he earned a degree in sociology from Mary Washington at a time when men on campus were few, and African- American men still fewer.

Today, Arline is 66, retired from a long career in law enforcement. He’s on the school board in his New Jersey town and is an active volunteer in his community.

He and wife Mamie have two grown sons – one a Navy veteran, the other a special agent with the Department of Homeland Security – and six grandchildren.

But there’s something else Arline feels compelled to do.

In December, he completed requirements for a master’s degree in divinity. His goal is an urban ministry to help African-American youths navigate a society they, and Arline, see as set against them.

“Young people in urban areas are faced with such horrendous obstacles,” Arline said, citing statistics about disproportionate school expulsion and incarceration rates for people of color.

“They see what’s happening. There’s no hope in them, and the system made it that way.”

Maybe he can’t fix the system. But Arline can help with the hope.

Surviving Battles

A guy Arline knew had joined the Marines, and when he came home in uniform he looked sharp. He talked about how tough and disciplined a Marine had to be, and Arline was hooked.

A week after he graduated from high school in Waterbury, Connecticut, Arline was in boot camp at Parris Island. That fall he married Mamie, his girlfriend since sophomore year. And in January 1968 he landed in Da Nang, Vietnam.

The Tet Offensive began within days, and the Third Marine Division, Third Tank Battalion was in the thick of it. The battles melded together, but somehow Arline made it through 13 months and 28 combat operations unhurt.

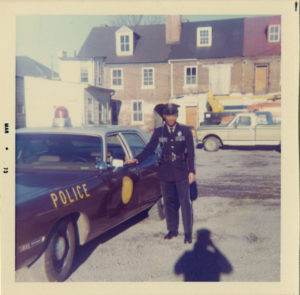

He ended his Marine service at Quantico and got a job as a Fredericksburg police officer, becoming just the second African- American policeman in the city. By 1974, he’d used the GI Bill to earn two associate degrees at Germanna Community College.

But he wanted a four-year degree, and in 1975 he transferred to Mary Washington as a junior.

The college had admitted its first black student only 13 years earlier and had accepted men just since 1970. But Arline felt welcome, and he found faculty mentors in William B. Crawley Jr., now professor emeritus of history, and L. Clyde Carter, a professor emeritus of sociology who died in 1990. “The professors were just gold. They really worked with me,” Arline remembered.

Despite family and work commitments, Arline participated in campus life as a member of the student Afro-American Association, recalled Sallie Washington Braxton ’77, now an associate dean in the College of Business.

“He always had his priorities in order, and he juggled so many things so well,” Braxton said. “You never saw him harried about anything.”

And when association members would get angry about injustice, she said, Arline would say something funny to break the tension.

His college friends might not have known it, but Arline had already faced plenty of injustice, right in Fredericksburg.

When his family moved to the city in 1971, they couldn’t rent in a white neighborhood. As a police officer, Arline once responded to a report of a fight at an all-white social club only to be stopped at the door while white officers handled the call.

And when Arline went to get his shoes shined at a barbershop his fellow officers frequented, the African-American attendant whispered, “I’m sorry. I’m not allowed to shine colored people’s shoes.”

Arline called on his Marine stoicism to persevere.

“I had learned how to survive in Vietnam,” he said. “I had been fighting for freedom and democracy for someone I did not know, and I wouldn’t let anything here deter me.”

A 33-Year Career

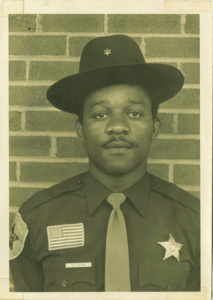

By the spring of college graduation, Arline was working as a deputy with the Stafford County Sheriff’s Office, and he got assigned to a case involving theft from mailboxes.

The U.S. Postal Inspection Service sent a representative to Stafford, and the inspector urged Arline to apply with the federal law enforcement agency. From 1978 until his retirement in 2004, Arline worked with the service in Atlanta, New York, and throughout New England.

In the early 1970s, Arline was a law enforcement officer in Fredericksburg and Stafford County, Virginia.

Even after his 33-year law enforcement career ended, Arline kept working. He substitute taught for a few years, then got elected to the Franklin Township School Board, a position he still holds.

He got certified as a suicide prevention specialist with the Cop2Cop program, providing support and grief counseling to fellow law enforcement officers. He was president of a chapter of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE). And he helped lead a chapter of Parents of Murdered Children.

In 2004 Richard and Mamie took in two teenage grandsons while their dad was deployed. That’s how Arline, a person of faith but not a devoted churchgoer, got involved in teaching Sunday school.

When one of the church elders asked him to become a deacon, “I looked at that person like they had three heads on their body,” Arline said. But he did it.

And as his church involvement strengthened, he heard a call from God.

At seminary, Arline concentrated his studies in pastoral counseling. And he recently agreed to become chaplain of the police department in Plainfield, New Jersey. He’ll minister not only to officers but to people in the community, especially young men.

It’s a group he already connects with through NOBLE, the law enforcement organization, as he presents a program called “The Law and You,” teaching teenagers how to act in encounters with police, how not to get arrested, and how to stay alive.

“It is regrettable that this type of education is required in 2015,” Arline said. But the recent police shooting death of Michael Brown in Missouri and death during an arrest of New York resident Eric Garner have made the program more relevant than ever.

Cases like Brown’s and Garner’s, he said, are just the latest examples of societal hostility that saps hope from young people.

In Arline’s youth, good people found a way to save him from despair. He knows he can save others.

“We’re really in a crisis right now, and that’s where I want to go,” he said. “I’m going back into the battlefield.”