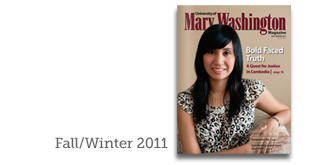

Sany Nhem (left) escaped Cambodia’s brutal Khmer Rouge regime in 1979 with her husband and eight children. She hadn’t returned to her homeland until her granddaughter, Fulbright Scholar Farrah Tek ‘10, accompanied her last year. The Fulbright grant supported a year in Cambodia for the U.S.-born Tek. She participated in an international tribunal to bring justice to victims such as her mother, grandmother aunts, and uncles. Photo by Reza Marvashti

Sophi Monh spent four years of her youth in a child labor camp hundreds of miles from the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh.

Monh was just 8 years old in 1975 when the infamous Khmer Rouge regime began its campaign that left a quarter of the country’s population dead. She worked from dawn to dusk, subsisting on one meal a day.

These are the stories Monh told her American-born daughter, Farrah Tek ’10, when she insisted her daughter take nothing for granted, that she seize each opportunity and work hard in school.

Monh spoke no English when she immigrated to the United States as a teenager in 1981. She did not finish high school.

Tek, deeply affected by her mother’s stories, set her sights on college and beyond. She majored in English and human rights at the University of Mary Washington and went on to earn a 2010 Fulbright Scholarship to return to her family’s native country. She took her Cambodian grandmother – Monh’s mother – with her.

Thirty years had passed since the fall of the Khmer Rouge, but its aging leaders had only recently begun to stand trial before an international tribunal known as the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, or ECCC.

Tek wanted to be a part of what she believed presented an extraordinary healing opportunity for those who had suffered her mother’s fate, and far worse. By age 10, Tek wanted to know more about the Khmer Rouge than what she gleaned from her family’s fragmented anecdotes. She turned to the Internet and library bookshelves.

What Tek discovered matured her. “While my peers anxiously waited for the next Harry Potter book, I researched the historical and political context leading up to the Cambodian genocide,” she wrote in her Fulbright application.

Though estimates vary, according to the United Nations at least 1.7 million people died in the Southeast Asian country between April 1975 and January 1979 from executions, starvation, exhaustion, forced labor, lack of medical care, or torture.