By Emily Freehling

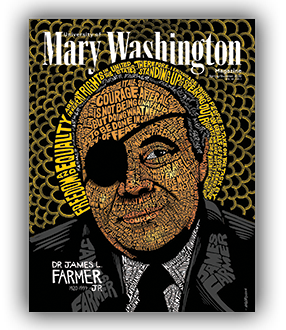

Nearly 500 people came to the University Center’s Chandler Ballroom in January to celebrate the 100th birthday of Dr. James Farmer, a civil rights icon who spent his final years sharing his first-person account of history with students at Mary Washington.

“Thirty-five years ago, he became a part of the Mary Washington Community,” UMW President Troy Paino said of Farmer, who taught the history of the civil rights movement at Mary Washington from 1985 until shortly before his death in 1999. “He left us a legacy.”

At UMW, 2020 is a year of reflection on that legacy. Former students remember Farmer’s deep, warm voice, which would at times burst into song. He captivated them with tales of fighting to change the status quo in Jim Crow America, and urged them to remember that the fight for equality and social justice has no endpoint.

“He was a human history book,” said Rich Cooper ’90, who not only took Farmer’s class but also served as his driver and personal assistant. Cooper recalled seeing Farmer as a giant of his age who would come into the room and provide “a first-person narrative of the sights, smells, emotions, fears, joy, turbulence, anger, and anguish of what he experienced.”

Farmer filled Monroe 116 – now renamed in his honor – for his lectures. Community members and students who weren’t enrolled in his classes were known to sneak in to get a glimpse of this man who made history.

“You took a journey through his words and he captivated you,” said Associate Vice President and Dean of Student Life Cedric Rucker ’81, who continues to use Farmer’s words as inspiration in the classes he teaches today.

While many alumni have carried Farmer’s stories with them into their careers and adult lives, Farmer’s legacy continues to reach current Mary Washington students through a curriculum he helped inform and a multicultural outlook he inspired during his 14 years on campus.

Farmer changed teaching

James Farmer’s connection with Mary Washington began on a Northern Virginia commuter bus in the early 1980s.

The late historic preservationist John Pearce, then a professor at George Washington University, struck up a conversation with a man he thought he recognized but couldn’t quite place. That conversation was the first of many Pearce would have with Farmer, according to an interview he gave in 2008 to an oral history class documenting Farmer’s impact on the university. Pearce joined the UMW faculty in 1984.

Pearce read early drafts of Farmer’s autobiography, Lay Bare the Heart, and once it was published in 1985, he helped bring Farmer on board at Mary Washington.

When Rucker joined the Mary Washington faculty in 1989, he was floored to discover that Farmer was lecturing at his alma mater.

“I am a child of segregation,” Rucker said. “The civil rights era was an era I lived through. Farmer was involved in the events that opened the doors for me to be at Mary Washington.”

A few years later, Rucker would see firsthand how Farmer impacted the curriculum at the institution.

Rucker had proposed to teach a class on ethnic studies that stirred faculty conflict over whether and how to adapt the curriculum to better reflect a world with more global connections.

The debate led to a meeting in which faculty members gave impassioned speeches about the course. Rucker will always remember the moment Farmer asked to be recognized. Using a wheelchair, the polished orator moved to the front of the room to speak.

“He talked about the importance of the course, why it was important to Mary Washington and the liberal arts framing of the institution, and why I was the person who should teach it,” Rucker said. “Dr. Farmer’s comments that day hushed the room.”

The course was approved, and in hindsight Rucker said the moment was a prime example of the power that Farmer’s life’s work brought to bear at Mary Washington.

“The colleagues in the room were willing to listen to him in a way that they weren’t really listening to each other,” he said. “It was really a powerful moment.”

From that point, the curriculum continued to expand, with courses introduced in women’s and gender studies – a program celebrating its 10th anniversary this year – queer studies, and other areas that Mary Washington had never before covered.

Farmer changed learning

Debby Sullivan Kelly ’91 was a copious note-taker in most of her classes. But she didn’t get far into her first lecture in Farmer’s class before she stilled her hands and opened her eyes and ears.

“I was taking notes feverishly, and then I found myself with my pen down because he was so captivating,” she said. “This was an experience that I was just going to immerse myself in and not worry about the notes.”

Kelly had not known much about Farmer before taking his class. After hearing the first-person account of this man who led the first sit-in in Chicago in 1942, she was struck by how much deeper the true story of history goes than the names that show up in textbooks.

Early in her career as an educator, she used Farmer’s autobiography in teaching a seventh-grade English class. She was heartbroken when a student took her signed copy, but she soon realized this individual might have needed those words more than she did. Here, she thought, was yet another young person whom Farmer could impact.

Today, as a librarian at Woodbridge High School in Prince William County, Kelly tries to find books for her students that explore history beyond the well-known figures.

“Farmer’s class made me think bigger about history,” she said. “It made me think about how a movement comes about – it’s more than a figurehead. There are a lot of people who put their lives on the line to make this happen.”

Farmer changed lives

In May 1961, Brenda Sloan was nearing her high school graduation in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. When she learned that a group known as the Freedom Riders would be stopping a mere 30 miles away in Greensboro, she begged her parents to let her miss school to join the bus ride.

The Freedom Riders, organized by Farmer, rode buses through the South that summer to test compliance with the Supreme Court’s 1960 ruling forbidding racial segregation in interstate transit.

“My father said it was a dangerous thing to do. Plus, he said, the school would not excuse me to go on a bus ride through the South,” Sloan recalled. “I felt that I had missed the bus.”

A few years later, Sloan had become active in demonstrations challenging segregation in restaurants and businesses in Durham, where she was a student at North Carolina Central University.

Sloan was jailed three times and nearly run over by a car. She experienced chilling fear when she and other college students blocked the entrance to a restaurant that refused to seat black people, and its owner emerged with a long rifle.

One day, she attended a rally where James Farmer was urging the crowd to use nonviolent methods to bring about change as he and other Freedom Riders had done. “It was such a huge crowd, he looked like a speck,” she said. “I never got close to him.”

That would change.

Sloan was an archivist and librarian at Mary Washington from 1983 until 2003. Shortly after Farmer arrived on campus in 1985, he called her to his office.

“The first thing I thought was, why does he want to see me? What did I do?”

Farmer asked her to help ensure that his autobiography was on file at the Library of Congress. The inquiry began a 14-year friendship.

Sloan got to tell Farmer how upset she was that her parents wouldn’t let her join the Freedom Rides. She got to hear him describe some of his most difficult moments, such as the time in 1963 when he had to lie in the bottom of a hearse to escape a lynch mob after a peaceful protest in Plaquemine, Louisiana.

Over the years, Farmer’s health deteriorated, in part from complications of diabetes: He lost his sight, and his legs were amputated. Sloan was able to give back to this man who contributed so much to the civil rights movement.

She worked with the Black Faculty Association to arrange visits to his house in Spotsylvania County to check on him and help with basic maintenance. She introduced Farmer to contractors within the black community, and many, when they learned who he was, performed repairs for him at no charge.

One day in December 1997, she was visiting her parents in North Carolina when she got a phone call. It was Farmer, making her one of the first to know that he would be receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bill Clinton in January. But there was a catch – she couldn’t tell a soul.

“I reckon my parents thought I was crazy,” Sloan said, because she’d been screaming with joy before hanging up the phone.

“They said, ‘What was that about?’ I said, ‘That was just a friend of mine calling to tell me something.’”

A legacy carried through words and deeds

Sloan and others said that as Farmer neared the end of his life, he had sought the honor of the Medal of Freedom. Despite being a leader in the civil rights movement and being on campus, Farmer still didn’t have the recognition among students – or the American public – that many felt he deserved.

“A lot of students thought the movement started with Dr. King in the ’60s,” Sloan said. “Farmer would talk about the first sit-in in the ’40s. He would say, ‘If you think it was dangerous in the ’60s, it was super dangerous in the ’40s.’”

Farmer retired as a distinguished professor of history and American studies in 1998. To this day, some of Farmer’s former students continue to look out for his legacy.

Cooper, who calls his experience driving Farmer to class “one of the greatest gifts of my life,” has been writing to the United States Postal Service for years trying to get Farmer on a postage stamp. He was part of a fall 2019 delegation from Mary Washington that visited Rep. John Lewis, a close friend of Farmer’s and fellow Freedom Rider and civil rights leader, at his office on Capitol Hill.

During that visit, Cooper spoke with Lewis while looking at a photo that included several major civil rights leaders. He pointed out that just about everyone in the photo but Farmer was already on a stamp.

Cooper was amazed that Lewis – on the first day of the House impeachment hearings – took more than an hour with the Mary Washington delegation. The group included Student Government Association President Jason Ford ’20.

Ford, from Culpeper, asked Lewis what today’s college students could do to continue the work of Farmer, Lewis, and the many others who contributed to the civil rights struggle.

“He said, ‘Don’t forget the fight that was fought beforehand,’” Ford said. “These leaders did not do this for it to be forgotten. There needs to be another generation of people to step up.”

Lewis had planned to headline the January celebration of Farmer’s 100th birthday, but he was unable to attend after receiving a cancer diagnosis in late 2019.

UMW President Paino, who also was at the meeting with Lewis, said the time the congressman spent with them was so extraordinary that it touched his heart and is “something I know I will take to my grave.”

Like Ford, he saw in Lewis’ words a call to action to keep Farmer’s legacy alive.

“I think we are getting ready to have a revival in this democracy,” Paino told the crowd gathered to mark Farmer’s birthday. “This next generation is going to get out and get involved to make our democracy stronger and better.”